Movies We Watch Again ... and Again - "McCabe and Mrs. Miller"

Why do we watch a movie more than once? Maybe we were so stunned by the film that, by watching it again, we can study it more deeply and gain more understanding of its riches. (For me, “Birdman” is a recent example.) Then, we might decide to see that same film yet again, because now our eyes can visit every part of the screen, pick up every background nuance, squeeze out every drop of meaning…

Other films we see may not stun us or challenge us, but seep into our emotions and go so deep that we well up or even weep, either with sorrow, or with a deep joy, and these films we re-watch not for the studying but… Well, it’s like visiting a dear friend for the comfort you know you will receive, and you want to feel that again.

For my second example of a film rewatched, I give you this post by a good friend and producer, Curtis Burch.

In the summer of 1971, I saw Robert Altman’s classic western “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” the day it opened. I was 16. I didn’t get it. I couldn’t see its images clearly and couldn’t hear the dialogue.

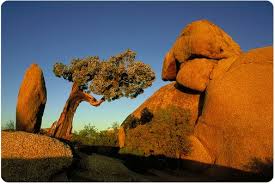

Pauline Kael’s rave review in The New Yorker motivated me to see it a second time a week later. Maybe I’d missed something. I had. The second time was like putting on a pair of stereographic glasses; suddenly I was being transported into the past, to a town I would, on many, many multiple viewings, come to know well. The town is Presbyterian Church, named after its most prominent structure.

For the longest time I returned to the movie over and over because I loved its mood and atmosphere made rich by D.P. Vilmos Zsgimond, production designer Leon Ericksen and songwriter Leonard Cohen. It wasn’t until later that I realized how drawn I was to the character of John McCabe (the great Warren Beatty doing his best work, though he’s always disowned the movie). McCabe is a unique figure in westerns. He’s handsome, charismatic and ambitious. He comes into town and rebuilds it to his own vision making a real success of himself as a saloon and brothel owner. But he’s not very smart and he loses his locus of power by falling in love with his newly acquired partner, the far more astute Mrs. Miller.

After a certain midpoint in the story, everything McCabe does is to try to win over the unreachable affections of the beautiful madam (the most luminous Julie Christie). The movie follows the sad, tragic decline of a decent man with poor instincts.

People have written about the movie as a metaphor for the flaws in American capitalism and it entirely works that way if you want it to. But mostly it’s just a beautiful heart-breaker. Everyone in the huge ensemble is great: Keith Carradine, Rene Auberjonois, Shelley Duvall, Bert Remsen, many, many others, including the entire crew who are building the town in the background, in costume, as the movie progresses. It was shot on a small plot of land against a hill in Vancouver, British Columbia. I visited the spot once, now fully developed with modern homes. But standing there, I could still pick up the spirit of the movie.

I continue to see it once every year or two. I went to a screening of it in Beverly Hills this past March at which Kathryn Altman, the widow, spoke eloquently about the experience of making the movie. Sadly, she died a few days later. I just recently bought the new 4K Criterion restoration on Blu-ray. I’ll never stop going to Presbyterian Church. For some reason that I still don’t entirely get, I’m irrevocably drawn to the sad descent of John McCabe.