Lake Town Christmas

Part Two

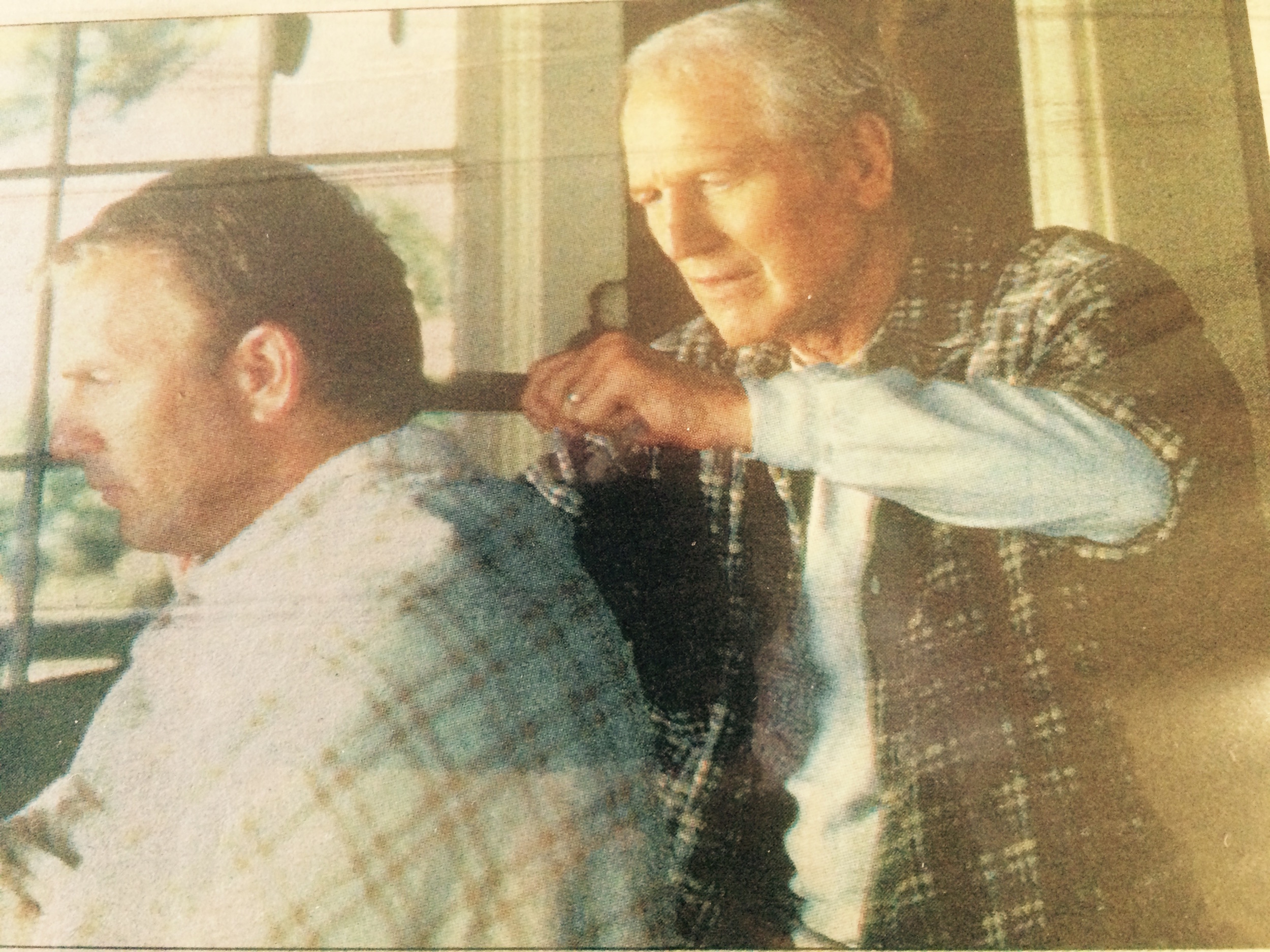

(The arrival on Christmas Eve of my mother’s family, visiting from Chicago at our home in rural Round Lake, Ill, 1950s: my favorite uncles, Motts and Tony, Cousin Jim and his new wife, Carolyn, my mother’s jolly sister, Inez — these characters described in last week’s post of Part One).

They moved into our home wailing and shouting and sometimes breaking into song – the tune of Auld Lange Syne with the words “We’re here because we’re here because we’re here because we’re here,” and I can hear them still, and hear my family calling out our own greetings, and broken bits of sentences were surfacing and disappearing as if in a swift river as they came deeper into the living room clutching bags clumsy with ribboned presents, but the presents were irrelevant to me even then, because the gift was themselves and the night to come.

The food, too, was unimportant. Tomorrow would be the meal around the table. This was bread and olives and prosciutto and salami and Parmesan, and drinks were made and a gallon bottle of red wine opened and the sofa and chairs filled so that my brother and I roamed or sat on the floor, and the stories rolled out and the jokes began and the teasing and the chaotic harmony of laughter, my brother smiling but cool and quiet at first and then, and I see this so clearly, buckling as if from a blow to the stomach, bending with silent laughter, his eyes squeezed closed, and my father smiling and chuckling as if he was watching a comedy on television and my mother giggling, giggling like a girl, and then making us laugh in turn by speaking in different voices and smoking her cigarette in strange, stagey ways, and I know now that a portion of my great joy in these Christmas Eves came as I saw my own family captured and changed, our silences abandoned, our seriousness deserted.

Once the visitors came in the door, I dropped all anticipation and expectation, and there was never a plan for what we would do. It was a kind of improvised theater where any topic could catch us up and fill the room with extemporized humor on its theme. “How’s college,” Motts might ask Paul, and Paul would say, “Fine,” and Motts would look at Tony, and they would begin: “Any knowledge at that college? What have they taught you so far? Tell us something you know. Did they teach you yet about the Sanafran? No? They didn’t teach him about the Sanafran. Oh, my God. If you don’t know about the Sanafran, how’re you ever gonna learn about the Spinowizz? I don’t think I like that college. Does it have a fight song? Let’s hear it.”

And Paul would try to sing it, his stomach hurting from the suppressed laughter until his eyes watered, and soon we were all singing it, and I can hear it now. I can. I can pick out each voice, the memory making me smile at this moment, and I’m feeling tears in my throat as if this one moment in this one chosen night has been distilled into a small amount of precious liquid, and I close my eyes and listen, because now Jim, the crooner, is singing us a song from the nightclubs, and when he finishes, he’ll sing another and then begin to do impressions of the singers of the time and then sing in comic voices and made-up languages and Motts and Tony will join him while my smile shines on them like a flood light

I never knew what would happen next, and never cared, never thought ahead and never imagined that I would remember so vividly those nights and treasure those nights, and that they would sustain me through yet unimagined tragedies and lift me whenever I studied my life for meaning or sense or tried to total the pleasure against the pain.

I felt no hurry in the center of that joy. I knew there would be time, as the night ran on, for quieter moments with each of the visitors, and I knew they would listen and even care what I said, and I watched them slowly sink from the shouted hilarity into a softer mood, Motts and Inez feeling the alcohol and mourning, with my mother, the loss of a brother. There was always a somber nod toward the ghost of Frank, but then the old stories would rise and all would rise again toward the laughter, and even my father would grow small, slow eyes from the drinking, a face of his I rarely saw. He was a solid man with little to say, and he had no play to give his children, no look that lingered and examined and searched for my dreams, nothing at all that could compete with these visitors except his solidness and his steady work and the security he gave us and taught us. I knew he sometimes loaned money to my mother’s family, and I had a sense, even then, that I was somehow safer with him, in spite of his temper, but how I fed upon the play that was sometimes in my mother and that always rushed through the door with these visitors who connected with a child and reached inside of a child and somehow preserved the children within themselves.

As the level of the wine sank in the big bottle, the conversations separated and softened, and I had my time to step away with Carolyn and speak of what we’d been reading, and she would ask me if I was writing and ask to see it, and really want to see it, and I would share it with her and with no one else, not because my family would have been harsh but only because they didn’t care to go where I went with Carolyn, to the place of stories, to the mind-created worlds that presented me with wonder like a talisman to keep and to wear, and I’ve always worn it and wear it still, and in time the drinking and the clock would press our visitors down into the beds and the foldout couches, and I never remember feeling sad but only filled as those nights ended, but, of course, they haven’t ended because I can live them again and am living them again as I make these pages, and they can never be erased, even by what came after, by the changes and the losses that came swiftly at the end of those years, by Tony’s death from cancer, and by Motts finding a wife who gave him a loving steadiness and a sweet daughter and moving with them to Texas, and by Jim and Carolyn divorcing, my Carolyn moving back to Louisiana, and Jim marrying again and having a family and becoming a machinist who would not give up his dream of singing so that he sang into the noise of the machines to keep his voice strong, and, slowly, time and death took them all away from me, even Paul, all except one.

In college I wrote to Carolyn, and we connected again and I saw her when I hitchhiked to New Orleans one Easter break, and it was a deeper pleasure than I ever imagined, seeing her again, her smile entering me and finding the place I had kept for her there since I was twelve and she came for the Christmases. We wrote steadily after that and even sent tapes of our thoughts, and she married and raised two children and so did I, but all the while there was Carolyn and me and the books and the films and the wonder we shared, a relationship that lasted more than fifty years until she died only months ago, and a love that will last until I die, and when I die, there will still be one last survivor of those Christmas eves, and that will be the boy, that eager boy who waited at the window and waited to hear the train, and that train will keep wailing and keep bringing him his visitors and his dream and the pure heart of joy again and again forever.