Sometimes They Let You Drive the Locomotive

I’ve been writing books and movies professionally since 1972, and most people don’t think about the research side of this work, but digging into the world of each script or novel can take a writer anywhere, everywhere, and I appreciate each journey I’ve made toward the authenticity, the human truth of what I’m writing.

Sometimes this exploration is exciting, eye-opening, heart rending, joyous, meaningful – and each piece of work I’ve done has benefitted from my seeing and touching the world of my story.

During the seventies and eighties, I was writing those network movies-of-the-week that are all gone from TV now, but I was lucky to be there when the business was so hungry for so much writing. Sometimes I wrote up to three of them a year, and each one led me somewhere, searching out some world for my study.

My journalism training and newspaper work helped me in this scouting for the reality of each world, and each journey broadened my life.

‘Runaway’ was a script about a train losing its brakes as it roared down the mountains, and I knew I’d have to write some key scenes that took place in the locomotive with its two-man crew, so the network called ahead and set up my visit to an LA train yard. The engineers were very cooperative. People generally enjoyed talking about what they do and showing me how it all worked. Before I left, the man in charge asked, “Wanna drive her?” Well, hell, yeah, and I did – just a couple of hundred feet, but it gave me a thrill along with a hands-on feeling.

Later I eagerly accepted an assignment to adapt a book called “I Heard the Owl Call My Name,” an award-winning Canadian novel about the native tribes living on the islands north of Vancouver and an Anglican Minister assigned to their church and school.

I was flown by seaplane to visit these tribal villages, sharing the sky with eagles, my first sight of them and only 30 feet from my window in the plane.

I so appreciated meeting the villagers, hearing the stories, the complaints and the joys and the day to day lives – and just taking in the rhythms of their speech, the way they moved. Being there and looking into their eyes added so much more value than simply reading the book.

Sometimes the journeys led me into the darkness and pain of a particular world, such as my 24 hour stint with a Santa Monica Fire crew, at the station and out on calls. I enjoyed the camaraderie of the station house admired their soldierly professionalism at work.

One call took us to the apartment of a woman having a heart attack. She was about 50, and once the paramedics went to work, she was soon talking them, to all the team, even to me, her wide eyes moving among us as she asked, “I’m going to be okay, now, right? I’ll be okay. I’ll be all right. Won’t I?” The medics spoke to her as they prepared her for the ambulance, telling her she would be tested at the hospital, and they would know just what to do for her. “But I’m going to be all right. Right? I know I’ll be okay.”

The last I saw of her was looking through the door of an emergency room as doctors, nurses, workers swarmed around her and someone closed the door. I followed the paramedics through their paperwork and asked them questions I needed to ask. As we were leaving the hospital we enquired about the woman and found out "She didn’t make it.”

I still see her wide eyes, full of that question, that final question.

I was hired to write a script about the juvenile prison system, a ‘School for Girls’ in New Mexico, and I was handed several newspaper and magazine articles to study. I was told we were going to shoot in an actual school, and I asked if I could go there now, before I started writing, and interview the staff and some of the girls.

I had heard, of course, how prison or reform school life can turn someone toward the dark side, create a hardened criminal out of, for instance, a girl who several times had run away from an abusive home. In many cases (back in the 70s) the abuse was denied by the parents and they willingly turned over their daughter to the system by making her a ward of the court.

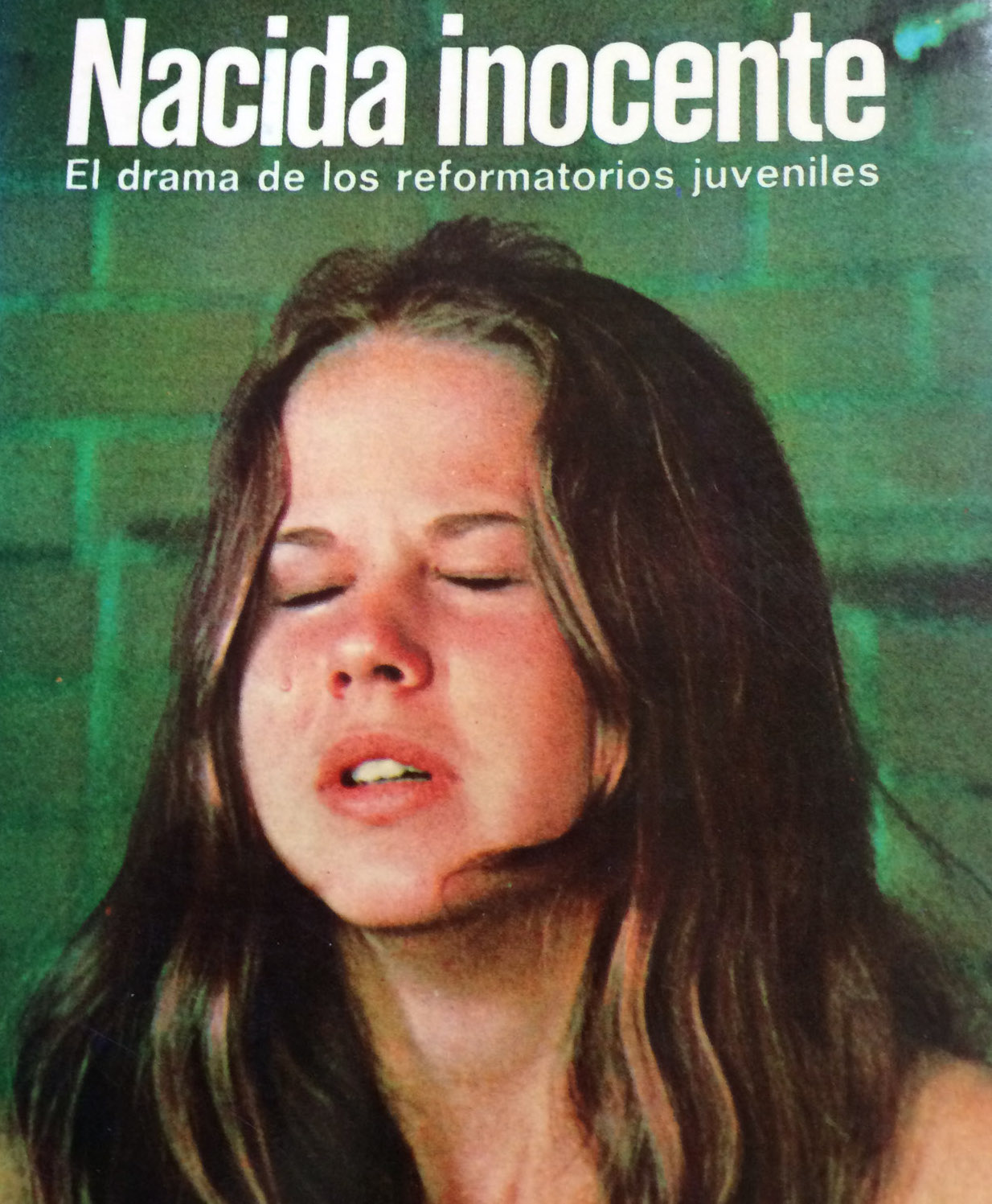

This is the story I wrote, called “Born Innocent,” starring Linda Blair, soon after her work in “The Exorcist.” From the staff and the inmates I learned about the girls who find themselves in the system and are initiated, sometimes brutally, by the worst of the inmates and made to live in fear, made to turn against their own personhood by cutting themselves, by a habit of pulling out their hair, and how they toughen and become rebellious and even dangerous.

Because I had been allowed to penetrate the veil of how these schools were thought to be and had seen and heard how they were, the film turned out truthful and gritty. Too gritty for some sponsors and some states where they refused to air it. The script was novelized and the novels were pirated in Mexico in a whole series of books called “Nacida Inocente.”

Linda Blair, Joanna Miles and Allyn Ann Mcleary delivered deep and fine performances, and the script was nominated for a WGA award – because I had been let ‘inside’ to do my research.

Film research has taken me to London, Kenya, Canada, and Washington D.C. ... but, more importantly, into the human truth of the people who live the lives we write about, and I’m better and wiser for it, and also convinced that there is a global brotherhood and sisterhood, and that the more we recognize this the closer we are to a much better world.