Coming Soon: A Night of Story-Telling!

Dear friends,

I’m so glad to announce a new show - it’s been a while! Please join me, Cynthia Carbone Ward and Sue Turner-Cray for a night of story-telling as we take you through our tales of imagination, laughter and pathos, all for a good cause, and at a fine new venue. See below for details and prepare for a good time! - Jerry

“TELL ME A STORY”

Sunday May 21st at 7:00 pm

An evening of tales written and told by three local storytellers! Have a glass of wine, get comfortable and enjoy the stories, beginning at 7:30.

Location: "The Grand Room," 181-D Industrial Way, Buellton (adjacent to Industrial Eats).

The Storytellers

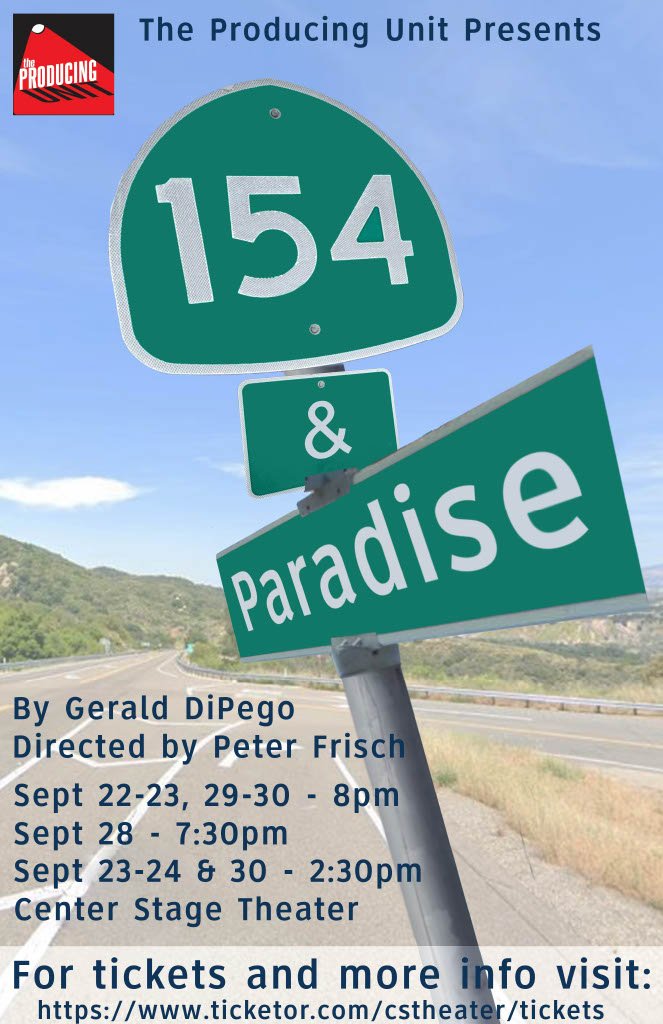

Cynthia Carbone Ward, author and writer of "Still Amazed," her continuing deep and humorous take on life. Sue Turner-Cray, actress, writer and performer of the knock-out one woman show, "Manchester Girl," other plays and TV film roles. Gerald DiPego, playwright and film writer: "Phenomenon," "Message in a Bottle," "The Forgotten," "154 and Paradise," etc.

This is a benefit for the Santa Ynez Valley Union High School PTSA. Tickets $20. Cash only at the door, please. Adult language.

Remote 2

The girl hangs over the right shoulder of a walking man. Her long hair blows gently in the wind. She is naked and her arms are limp and swaying slightly as the man trudges on. It’s nearly night, and his way is broken as he moves around trees and fallen limbs, stopping once to reset the body he carries, then moving on. He stops once more to pull a small flashlight from his pocket, turn it on, and continue his walk, his search, while the limp girl moves in a kind of loose dance to his steps. He nears an old and unlit building and stops.

In the afternoon of the following day, several towns away in Indian Lake, Illinois, Leonard Defore is building a fence. Just for the look of it, he will say, if anyone asks him, but no one is likely to ask. The real reason for the fence is that Leonard needs the work, the hard and heavy labor. He enjoys this and is glad for the muscles that swell his arms and shoulders, but his primary motive concerns sleep. As always, he enjoys the work and is glad for the muscles that swell his arms and shoulders, but his primary motive concerns sleep. If he has a taxing physical project, he will sleep well and, most importantly, he will not dream. This way of staying dreamless has caused the house to be newly painted, a shed built, more than enough firewood stacked and even the wheel barrow to once again shine a bright red.

He has, over the years, seen his daughter grow and leave the home, and then his wife also in time, and now at 54 he’s been alone for eight years, though his daughter visits. He is an accountant who works out of his home for the people and businesses in the town, and he is also a known "remote viewer." Now and then, sometimes after years of not dreaming, he’ll have another episode, where he sees, in his dream, something that is happening, actually happening, somewhere else in the world, sometimes as close as the town where he lives. Twice, he has used such a viewing to help the police solve a local crime, and this has set him apart and caused a loner to be even more alone than he wishes.

His phone is ringing now. It is likely a client calling. But as he reaches for it, he feels a small tick of worry that it might be someone who wants to know about his “gift,” his remote viewing, a reporter, someone writing a book, or someone who has lost something and wants him to dream where it is. He sees the name of Betha Kane on his phone. She is a police detective in the larger town of Waukegan, and, yes, he helped her solve a case here in Indian lake, nearly six months ago. He is hoping that she has thought long about it and now wants to continue the two-date relationship they had before she stepped back, but he’s afraid that this is police business again, and she will try to pull him into it, just as he is trying to end it, end the viewing, end being that odd man in town who gets those looks. Will he ever erase those looks? Still, he finds he wants to hear her voice, come what may.

“Hey, Betha.”

“Leonard, hi. Have you heard about what’s going on here, the murders, the ‘Hide and Seek Murders’ they call them?”

“I’m fine, Betha. Thanks for asking.”

“Okay, I’m pushing this, Leonard, I know. But it needs pushing. Do you know what I’m talking about?”

Well, Waukegan is a long way off. Must be almost fifteen miles from the lake towns.”

“So, you’re still mad at me. That doesn’t matter now.”

“I’m not mad. I was never mad. Just disappointed.”

Well, get over it. Or don’t. It doesn’t matter now. What matters is another girl is missing and we found her clothes, just like the last three. He puts the clothes out where they’ll be found, like some kind of goddamn trophy. But he hides the bodies, and by the time we find them they’re decomposed, and we need a fresh body to stop this son of a bitch. We have a suspect this time. Prime. I’m betting on this guy.”

“I haven’t dreamed in a long time. Well, not that kind of dream. I dreamed of you a few times.”

“Four girls in three years. Four families gutted, and you’re talking about us?! Come here. I’ll take you to the places where we found the other bodies. I’ll show you photos of the girls, of this girl. Liya Pope. She’s 17. I’ll pay your expenses, get you a room somewhere. Give it some days and see what happens.”

“Your department wants me to come, to get involved in this?”

“No. It’s just me. Nobody’ll know what you’re doing. No reporters. No cops. Just us.”

“I don’t see how you can hide me, Betha. From your team?”

“I’m . . . not on the team. I’m officially off the case. It’ll be just us . . ."

“Off the case? What is this?”

“The suspect is a hothead. I got in his face and he put a hand on me, so I punched him in the throat. My captain says I overreacted and so I’m off the case. I’m doing this on my own because we have a chance, Leonard. I handled the last two of these killings and I want this to be over. Forever. Will you please come here?!”

He pauses, but he knew from the beginning he would try to help her. “Will you tell me, please . . that your expectations are very low on this, Betha? Do you know the odds?”

“I know the girls are dying. That’s what I know.”

He arrives in Waukegan the next evening. She meets him at the motel where she has booked him a room. It’s not quite seedy. She apologizes, but he’s not really listening, just studying her brown skin aglow under the cheap ceiling fixture. He’s remembering her hard-won laughter that loosened him like a drink, her smart, sarcastic smile when she gave it, remembering the one deep kiss that she had interrupted as she stood back from him, shaking her head, truly sorry, he saw, but firmly shaking her head. How did she say it? “I’m all job, Leonard, and I’m aiming for the Chicago force in a year and . . . ”

He had asked if there was someone else, and had hated watching her nod. “Cop like me. It’s a secret thing. It’s just . . . something we do and walk away from, and I know you want more than that, and I can’t.”

He had said, “Try me,” and she had stared a while, and then her damn head was shaking as she told him, “You’d want more, and maybe I would, too, but I can’t do it now. Can’t step off this road. Sorry.”

Remembering all this, he asks her now, “Tell me – is it the dead girls, just the girls, or do you want this killer for your plan, for Chicago?”

Her stare goes even deeper, and she takes her time and says it softly. “It’s the girls.”

He nods, tossing his suitcase on the bed. “When do we start this?”

“There’s a diner across the road,” she tells him. “It’s not very good, but it’s quick. I’ll pick you up there tomorrow morning at 8:30. Meanwhile, I’ll leave you these photos, all the girls including the one gone missing now and details about the cases. Look at them here. Not at the diner. You’re not supposed to have access.”

He nods. Now the goodbye. Will she take a step closer? No. She moves to the door, opens it, turns to him, sighs. “You ready for this?”

“For this longshot,” he says. “Yeah.” He nods, she nods, and it’s over, and he’s alone.

In the morning he’s in the diner, finishing his breakfast as he watches one of the servers, a young man who isn’t bringing anyone’s meal, but asking about coffee, juice, a refill . . . Leonard is caught by this man’s dance-like movements, as he dips and turns and uses his hands to underscore what he’s saying, holding one hand as if it is a cup as he asks his question, then dipping, turning, his hand now holding a glass that isn’t there. “Juice, señor?”

Leonard sits with the last bite of pancake on his fork, held by this man – who is then blocked by Betha’s body as she appears at his table, staring. He looks at her, at his watch, says, “You’re ten minutes early. Want some coffee?”

She ignores the question and sits lightly on the opposite chair. “Did you look through everything?”

“I don’t look at decomposed bodies. I draw the line there. What the hell is that supposed to give me? I looked at the photos of the girls as they were. You trying to shock me?

“Yes. Let’s get out there.”

He finishes his coffee, pays. She says, “Keep the receipt. I’ll catch all this at the end.”

In half an hour they’re at a dirt road with deep ditches on either side, and Betha is pointing into a ditch, saying “Mary Beth Oldham. He didn’t exactly bury her. He didn’t dig, just put her in the ditch and covered her with leaves and branches, and all that piled up over time and then was washed away in our biggest storm, and she was uncovered. This photo . . . here.”

He doesn’t look at the photo she holds. Instead he checks one that Betha has given him, the girl when she was alive. Sixteen. A deep and true smile. He steps into the ditch, staring, asking, “So she was face up?”

“Yes, why?” But he only stares into the ditch and again at the photo, and Betha says, “We found her bike right away. We think he was following her in his vehicle and then bumped her to knock her down, then put her in the vehicle and came down this old road, found a secluded spot and raped and strangled . . . Well, you read all this, right?”

He nods, still looking into the ditch. “You think he might have killed her here?”

“Possible. She’d been missing for over eight months.” He nods again, then looks up, toward what she might have seen, the last of what she would ever see. “What do you think?” Betha asks him.

He brings his look to her and says, “We can go to the next one.”

Isabelle Woo had been hidden under a fallen tree, the tree propped slightly off the ground by other deadfall. She had been 15. Willowy. The photo he holds shows her laughing. Leonard kneels at the sight, stares at everything, imagines everything. When he rises and brushes himself off, Betha says, “Feeling anything?”

“Don’t keep asking,” he says. “Okay?” She nods and he goes on. “This is all just . . . Just in case I dream. Thousand to one, all right?” They walk to where she has parked. “Where now?” he asks.

“I have things to do. I’ll pick you up at the motel at ten tonight. Take another look at the girl, and the suspect’s photos, Dan Melios, and his sheet. I’ll bring you to where he works, a restaurant bar. Kinda seedy. He’s the bartender. You can study him. He’s been incarcerated twice."

“I have all this, Betha. I’ll take a look.” But she goes on.

“He was seen with Liya at the bar, where she used a fake ID, and he busted her, but they were smiling, people said. They talked a while. Then, when he closed up around midnight she was out there, waiting. One of the workers saw them, and the suspect confirms that, says she walked him to his apartment, said goodbye and he never saw her again. Just a kid, he said, and he said she was funny. Funny. Melios came to town four years ago. Just before the first girl went missing. I know you read this but read it again. It can’t hurt. And read about his convictions, assault and battery, one of them . . . ”

“One of them a woman,” he says. “I know, Betha. I read every word and I’ll go through it all again. Drop me here, and I’ll walk the rest.”

She pulls over, staring at him. “So I’m pushing you. I know . . . ”

He’s already opening the car door, saying: “I’ll see you at ten. And don’t come early,” and he walks on and she watches him.

Later, in the car, on the way to the restaurant-bar she begins schooling him again. “This girl is exactly, exactly the right fit for the ones he’s killed, the age, the size. He takes a big chance here, ‘cause he knows he’s been seen with her, so . . . I’m thinking maybe it was not planned this time. She was a target of opportunity. We’re here.” She parks across the street from a neon sign: “STALLS.” “Ben Stalls is the owner. Our guy Dan works the bar until they close at midnight. He acts as bouncer too when he has to. He’s a boxer. He was. Welter weight. Eight legit fights until he was arrested for assault and battery, and that killed that.”

“Okay. Got it.”

“Study that asshole, go deep . . . so then maybe . . . ”

“Look, Betha, you’re in my territory now. My goddamn dreams. I’ll watch him. I’ll leave, and we’ll see what happens. You can back off. You can wait.”

“Yes, sir,” she says – and they hold on each other’s eyes for two seconds and he’s out of there.

Dan Melios seems to be the perfect bartender. He’s quick, knows his drinks, cracks a handsome smile now and then, but the smiles are tempered. Something on his mind. He has a boxer’s scar that splits one eyebrow, looks like he works out, sends his glance all around, looking for trouble? It’s one of those places with three screens, no volume, all sports, and Leonard, after ordering his whisky tonic, watches a game of cricket, Afghanistan versus . . . He can’t catch it. Dan brings him a nut dish. Leonard nods a thanks to the possible killer of four young girls and sips his drink, eats some almonds.

In the mirror he watches some of the meager patrons. A man two stools down reacts to one of the screens and turns to Leonard, saying “You catch that?! Jesus!”

“Missed it,” Leonard says and looks at his drink with his eyes glancing at Dan now and then. Looking for what? Just looking, just pinning the man into his brain. He tires of this and looks at himself in the mirror and tires of that, too. He wishes the man from the diner was here, the fluid young man dodging and turning and doing a kind of mime dance among the customers, and then he has an odd thought that surprises him. He thinks, what if he were that man? Life would be so simple, wouldn’t it? What if that was all he had to do, that dance, asking with his whole body, bringing the coffee, cream, tea, juice . . . and dancing off again. He lets himself wish that for a minute.

After two hours, one taco and too many drinks, the place begins to shut down around him. He notices, but waits for the bartender to tell him, wanting that contact to help pin him. “Closing out, buddy,” says the ex-boxer. And Leonard nods and pays, taking his time. He steps outside the bar and enjoys the coolness of the night. He lingers out there a moment, and is surprised to see Dan leaving, while others are still cleaning up inside.

He likes the man’s shoulders-back kind of walk. What does he see in that walk? A peacock? A readiness? A challenge? That’s it, a walking challenge to the world: so what I’m an ex-con, ex-boxer . . . whatever else I am, whatever I’ve done, whatever I haven’t done, so what? Here I am. There might be some anger in that walk, and maybe that anger needs an outlet, four outlets in three years, four young girls who had to pay?

Leonard finds he’s walking behind Dan, about fifteen paces. He didn’t mean to follow him, but it’s a good study. He probably wouldn’t be doing it if it wasn’t for the drinking, but he shrugs that off. He’s letting Dan teach him all about Dan. This could be good – for the possibility of a dream, but he shouldn’t push hard on that, has to let it come, just come. Dan has turned a corner onto a darker, smaller street. Leonard could stop now, stop and call Betha and report, but he has nothing to report, so he finds himself turning the corner to follow the killer-diller.

As Leonard turns the corner, he is grabbed – two strong hands balled in his jacket – and he is pushed hard against the door of a closed laundry, his head bouncing off the door. Dan Melios, teeth bared in anger, pulls Leonard toward him and then bangs him back against the closed door again, saying, “You a cop?! Ha?!”

“No! I . . . ”

“You followin’ me?”

“No! I just . . ."

Melios sends a hand to Leonard’s throat, choking off his words. “You a fucking private cop? Ha?” His hard grip doesn’t allow an answer, and then he withdraws his hand to slap Leonard, bloodying his nose. He’s at his Leonard’s throat again, digging in, furious. “I seen you watchin’ me in the bar, asshole!” When he slaps Leonard again, the bigger man shoves Melios back a step, but the boxer hits him in the forehead with a hard jab and grabs his throat again, and Leonard feels the pain and shock and something else. He feels like he might die, this man might kill him, and he thinks, in a quarter of a second, about the girls, battered and choked, and along with the pain and fear, anger shows up, and hate.

He sends both his large hands to Melios’ throat, and now the smaller man is choking, and Leonard turns and pushes himagainst the building and then turns him around and throws an arm lock on his throat from behind, and the man is trying to tear at that arm, kicking backward and flailing his hands wildly now, and Leonard feels the man’s panic and thinks – is that what the girls felt? And he wonders if he should do it, make this man die, and then all of this would end. But Melios’ movements are weakening, and Leonard relaxes his large arms and shoulders and lets the man slide to the sidewalk where he falls and breathes like some broken engine, sputtering, coughing. Leonard watches the boxer, then steps away, heading for the lit street and the way home.

As he walks, he calls Betha, then thinks he should have waited, so he would have more breath.

“Sorry . . . to call you late . . . ”

I was waiting for it. You sound . . . ”

“Yeah, I’m out of breath. I was following him home . . . just to see him, plant him . . . in my mind, and he turned on me. He hits hard.”

“Oh, shit! He beat you up? Where is he?”

“He’s on his ass . . . and I’m walking away.” Leonard turns to look behind him.

“He’s not following, and I’m going to change streets, just in case . . .”

“You weren’t supposed to get in his face! Now what?!”

“He doesn’t know who I am. Nobody saw us.”

“Tell me where you are and I’ll pick you up.”

“No. No, I need the walk.”

“Leonard, It’s miles.”

“I need the walk.”

The dream lingers, unchanging. A fence? He is looking through what seems to be a rusted fence, and beyond it is darkness, but with . . . pinpoints of light. And somehow . . . the top of a tree? Swaying with the wind? There’s no logic, even to the placement of things. But this is not an ordinary dream. It’s not. It’s a viewing. He feels that. He wakes and sleeps again and then his cellphone wakes him, and he’s pawing the phone off the night stand, glancing at the clock. It’s nearly noon. He says “Hi.” but the word is broken and he tries again, clearing his throat.

She asks, “How do you feel?”

“Said the woman to the punching bag.”

“Did you dream?”

“There was something.”

“Describe it.”

“I need some time. Too groggy.”

“We have him, Leonard.”

“What?!” He sits up in bed, moving through the pain from the punches he took.

“They went in with a search warrant this morning. They found a kind of coin purse, a woman’s coin purse made of leather. Scratched, beat-up. They sent a picture to the girl’s parents. It was hers.”

“Jesus.”

“Found some drugs there, too, and there were hairs in the bed, her color. He knew he was busted, so he admitted she was there twice over the last week. Drugs. Sex. He’s still denying murder, but he’s shaky as hell and he’ll crack wide open. Go dream about that fence and we’ll hit him with everything.”

“What did he say about me? About the fight?”

He just said some big white guy jumped him in the dark and he hit the guy and ran home. You put some major bruises on his neck, and you should hear his voice. You almost killed him, for god’s sake, Leonard.”

“Maybe I should have. For a second I wanted to.”

“Don’t you say that. Don’t be an idiot. He’s done. We’ve got him. Listen, I have to go. They’re questioning him again, and they won’t let me in there ‘cause I was taken off the case, but I can see and hear what’s going on. Call me when you get something.” She hangs up, and he knows he can’t sleep anymore. He puts his feet on the floor and rises slowly, wincing at the pain. He needs an ice pack. He needs some breakfast. He needs to remember.

By late afternoon he feels the tiredness coming back, moving through him. He sits in the one cushioned chair in his room and closes his eyes, but that’s not doing it, so he moves to the bed, lies down, stretches out, looks at the ceiling, and, in time, he’s there again, not dreaming, remembering the dream, but, no, not a dream, remembering the viewing. He’s certain now, continuing to stare upward as the ceiling disappears and he’s staring through that rusted fence or . . . grate, staring upward. That’s it. staring up at the sky, the night sky. Staring up like the murdered girls were staring. He feels his heart increase. He is lying down somewhere. It’s cold. He is looking up at the sky – through a rusted grate. Those points of light he saw – they’re stars, and there is the tree, just the top of a tall pine, moving slightly in the wind, and he realizes he’s not himself. His heart pumps even harder now, as he comes to feel certain, certain that he is looking through the eyes of someone else. The killer? The girl before she died?

A grate in the ground means a building somewhere – a place near trees, a place where nobody goes. Abandoned place? He tries Betha, but she doesn’t pick up. He asks this of the motel owner: abandoned building in some forested area, and she sends him to one of her permanent guests, an old man, threadbare man. “Used to be some buildings in the woods north of town. Used to be a . . . Well, there was a school out there for years, but that shut down. Atrem Road runs along the woods there. There was a sawmill, too, but they carried most of that away when they moved the operation . . . ”

He calls while on his way and lets Betha know where he’s going, lets her know about the grate, and she is excited, shouting in a whisper. “Oh, god, if it’s there, if the body is there, he’s done, Leonard, he’s finished.” She gives him clear directions to the abandoned buildings and says, “This is coming to a head now, and they’re going to let me have him, Captain said. They’ve set him up and I . . . But I’ll get to you as soon as I can, and meanwhile I’ll call the person who’s leading the search for the girl and tell her I got an anonymous tip, and she’ll send people out there . . . Leonard? Watch for the . . . ” They were losing their signal, and he found himself speeding, pulling toward the forest, the buildings, the grate . . .

In twenty-five minutes, he’s leaving the sight of the old school, no grating there. He drives on and sees a nearly weeded-over entrance into the forest and takes it as far as he can, then leaves his car and hurries on, his chest tightening as he comes upon what is left of the old sawmill. He feels a pull, a definite pull as he hurries around the half-fallen structure, watching the ground, seeing no grate, then he pauses, slowing his breath. He looks above and sees the trees, tall pines, just as in his viewing. He moves around the structure again, more slowly.

When he sees it, he stands still for a long while, an old, rusted grate in the ground. He knows it’s the one. And he knows someone is in there. He feels that and takes three, four steps. He points his flashlight as he reaches the grate, points it down. It’s her. Liya Pope, and she’s lying on her back, her face pointing upward to the grate, to the late light and the high trees, and she is naked and bruised about the neck, her eyes closed, almost peaceful, he thinks. He curls his fingers into the grating and lifts, and then tosses the heavy metal away into the weeds. She’s about six feet down. He puts his flashlight in his pocket and steps to the edge of the hole and turns, bracing his hands on the ground and then letting himself drop, landing on his feet just beside her. He retrieves his flashlight and studies her, studies her mouth which is slightly open, studied her breasts and doesn’t move his eyes, doesn’t move the light, and he sees what he would not let himself hope to see. He sees the rise of a slight and slow breath.

He moves close to her and speaks her name, touches her face, again, again. The eyes open slightly, not focusing, not seeing him. He takes off his jacket and covers her, studying her face one moment more, wanting to shout, to weep, but he turns to the side of the hole and leaps upward, looking for purchase on the edge, but it is slick and he falls back inside, falls beside her. When he stands again, he hears movement on the surface of the ground, steps, moving slowly, moving to the hole, and he holds his breath.

He sees a tall uniformed police officer reach the edge of the hole and fill it with the glare of a very large flashlight. The cop changes the light to his other hand and draws his gun. Leonard has his hands above him, shielding himself from the wash of bright light. There are more footsteps above now, and people calling out, and the cop says to him, “Who the hell are you?”

And Leonard says, “She’s alive.”

Forty minutes later, Betha arrives. The girl has been taken to the hospital, but the area is still full of police, lit brightly now, a dozen squad and detective cars parked at odd angles as a team studies the area. Leonard sits on the ground, leaning back on one of the cars. He is handcuffed and sore and dirty and so glad, so glad because the paramedic had said, “She’ll make it,” when he asked him.

He watches Betha coming toward him, sees her intercepted by a female police sergeant who points at him and says to Betha, “So, detective, he says he knows you?”

Betha nods, not breaking her stride toward him. “Yeah. He’s with me. Take off the cuffs.” In a moment he is standing, rubbing his wrists as he and Betha hold their stare. No one can overhear them now.

“I have to tell the whole story to the Captain, Leonard. I don’t think he can keep you out of it. Sorry.”

He nods wearily, sighs a long sigh. “Just so she stays alive.”

“I’ll be busy here a while,” she says. “Can you make it back to the motel?” And he nods, and she keeps her deep stare on him. “Thank you, Leonard. You hear me? I’m saying thank you, from all of us and from her parents, and . . . That doesn’t say it all. Not even one little piece of it.”

The stare holds. He nods, then starts his walk to the car. She waves a cop over and tells the man to walk with him and make sure he can pull out of there. She watches Leonard until he’s out of sight and keeps staring in his direction.

She doesn’t come to the motel until three hours later. He’s packed, lying on the bed, dozing, until she knocks, and he rises and lets her in. They sit at a small uneven table, both weary, but she still carries that same deep stare for him, and she tells him, “She came fully awake in the hospital. She knew her attacker, knew of him, one Thomas Trasker. He has a three-truck rodent business in the town, for years. He even ran for city council once. Almost won. We knocked on his door. He was home with his wife, teen kids. We asked him about Liya Pope, and he fell on the floor, literally, fell to his knees. You should have seen the looks – the wife, the kids. They knew zero about this, of course. What a scene.”

“Melios?” he asks.

And she says, “Happy man. Not just free. Happy she’s alive. Happy tears. I think it’s true love.” They both grin a bit, and then grow serious again. Betha doesn’t know what else to say, so she says, “Let’s settle up. Give me your receipts.”

“You already paid the motel, that’ll do it.”

“Leonard . . . you know what I owe you, what this city owes you.”

“I don’t give a damn what Waukegan, Illinois owes me. It’s what you owe me.”

“What? What can I say?”

“Nothing. Not a word. I want just one thing for all this. You ready?”

She nods, wondering, and he says, “I want to finish that kiss we never finished, ‘cause you stepped back.” He’s completely serious, hard-looking about this.

She’s quiet a moment and then begins to shake her head. “I told you then, Leonard, about what I need to do, about the Chicago force, and . . . ”

“I’m not talking about the goddamn future. This is about the past, Betha, about that one kiss, that’s all. I want it in full, a long one, a deep one. I want us to finish it.” He stands up then, and waits.

She stares a while, then also stands, looking tough about this, but her eyes are moist. “Tongue?” she asks.

“You bet.”

“Hands?”

“Just on your back. Ready?”

Another long stare, and then she takes a step closer, and he moves in and it’s on, deep and tight and long, as they press together and his hands are on her back and in her hair, and she’s kissing him back and hard, and is in his hair now, and there is nothing still, not for a second, but all moving, and moving, and moving, two mouths as one mouth, tongues like slippery creatures, mad creatures, on and on, and when they finally break, they’re out of breath, staring hard again, almost moving into each other, but not. Not. He slowly steps away, then moves to the bed where his suitcase lies. He picks it up and walks to the door, not looking at her. Her eyes drop two tears as she watches him.

As he reaches the door and opens it, there is a war inside of him: say something, kiss her again, wait, but he takes a full breath and opens the door wider, thinking he wants her more than anything, but, hey, listen, the woman has Chicago on her mind.

Stand-Off

July already? Here’s this month’s story, taking you to rural Illinois on a day when anything can happen and the future is in doubt!

STAND-OFF

By Gerald DiPego

We’ll call the place Perch Lake, Illinois, and the time is around 1:30 in the afternoon, early summer, 2011 or so, and what we’re watching is a man about the age of 80 driving a truck so dented and rusted and rattling it must be traveling on plain spit and spite. The driver is Chester Nash, former roofer who took a fall, former farmer who gave it up and sold off most of his land, former celebrated high-school athlete who gained 48 pounds since those days, and former infantryman in a war that’s so seldom mentioned these days, you’d think it never was, but it was, and he left his youth and some of his friends and some of his blood in the country of Korea.

Chester parks the truck in front of Tip Top Foods, a smallish two-checkout grocery, its windows jammed with sale signs and posters for the town’s ‘Summer Blast’ and the Fire Department’s Carnival, and the Rotary’s Picnic, all of them out of date.

Only a few customers inside, and some nod to Chester, but he doesn’t seem to notice, moving toward the items he wants, carrying one of the plastic baskets and filling it as he’s watched by the store owner who stands operating the only active checkout, and this is Arnold Tattimer, who is 66 and thin and normally suspicious, but now expanding that part of his nature as he watches Chester pass up the cold beer case and reach high up on the wine shelf to take down a bottle of the store’s most expensive California red at forty dollars a pop.

This is a first, and raises Arnold’s worry, but he has to stay put and check out the items on his counter. By the time he’s done, his employee, Lonny Pulaski, returns from her break, and Arnold is free to spy on Chester, whom he sees just leaving the meat counter. He investigates and learns from his butcher that Chester has NOT bought his usual chicken wings and ground beef but chosen two healthy cuts of filet mignon. This is also a first, which quickens Arnold’s pace, coming upon Chester as the man places a box of cookies in his basket, the store’s most expensive chocolate-covered brand imported from no less than England.

“Chester,” Arnold says. “You sell off those two acres?”

Chester barely glances at the man, ignoring the question, moving to the produce for beets and broccoli and then making his way to the front of the store. Arnold beats him there, and when Chester arrives at the checkouts, Arnold says to Lonny, “I’ll check this one out,” and moves to the machine as she backs away. And here comes Chester with his heavy basket, not even pausing, not even glancing at Arnold, but simply walking out of the store, basket and all, getting into his truck and driving away, as Arnold, outside now, shouts something about the police, but Chester’s truck is making too much noise for the words to carry.

About forty minutes after Chester’s getaway, a county deputy is pulling into the driveway of an old well-kept home with a thriving garden and a water element. The deputy, Tom Basco, around 25, walks quickly to the door and rings the bell. The door is opened by a smallish women of 84, wearing a summer dress, her white hair well-kept, and her eyes rather penetrating. She is one-half Native American, and there is a question in her manner, seeing the deputy at her door. Her name is Ella Dawn-Netter, and while she was teaching at the Perch Lake High School, before she married her fellow teacher, John Netter, she was called Miss Dawn, but the name soon morphed into ‘Mizdawn’, and even throughout her marriage with Mr. Netter, now deceased, she was called that name. She taught history to generations of local teenagers for nearly fifty years, and if there is another quality about her, beyond her knowledge and her depth, it would be called no-nonsense.

“Mizdawn, I’m deputy Basco, and the sheriff sent me out here to ask your help. It’s an emergency, and I’m to take you out to Chester Nash’s house.”

She stares for one second, then “Deputy, what’s the emergency? Why am I needed? I’m not a doctor, and I don’t suppose I’m to go out there to teach history, and why didn’t the sheriff call me to see if I’m available, which I’m not.”

Basco takes a breath. “Nash is holed up in his home, and he has a gun, and he…he robbed the Tip Top store and says he’s not coming out, and the sheriff said…” But Mizdawn interrupts: “Why would Chester rob a store and then go home?” “Well, Mizdawn, he’s cooking in there. He robbed groceries and…” “Wait, you’re saying he stole food, and he’s cooking it?” “Yes ma’am. And he says if anybody comes close to the house, he’ll shoot’em.” “And the sheriff wants me to go ‘close to the house’ and do what?” “Well, you can stand off to the side, where he can’t shoot you, and talk to him. Make him come out, or…toss out that gun.” She shakes her head in wonder and says, “Let me talk to the sheriff. Shall I call him on my phone, or…?” “Mizdawn, there’s no time. Gotta go now. Sheriff’s real busy out there. I have to bring you.” “By force?” “Well…Ma’am…I gotta bring you. Now.”

Mizdawn sighs, straps on her purse, locks her house and is taken away in the deputy’s car. They’re speeding toward Chester’s home when Basco says, “So…you were a teacher here?” “Yes, you’re not a local boy, are you?” “No, ma’am, and you… they say you’re part Indian?” “You mean Native American, deputy. The Indians are people from India.” “Oh, yeah…. What tribe?” “Potawatomi. “Uh-huh, never heard of ’em. Where they from?” “From here. Right here. Until they moved us out. Long time ago. Almost two centuries. Do you really need this awful siren?”

When they arrive near Chester’s home, there are four police cars scattered about and four other cars and trucks further back from the house with people outside their vehicles, watching and waiting for something to happen. Mizdawn spots the sheriff hurrying toward the deputy’s car as she is stepping out. The sheriff’s name is Esther Ramirez, and Mizdawn notices that though she’s a bulky woman she moves quickly. “Come this way, Mizdawn,” she says, and leads her toward the side of Chester’s old house, which is badly patched and crying for paint. “Thanks for coming out here,” the sheriff adds, and Mizdawn says, “I had no choice. I don’t know what the hell I can do for you, Esther, and keep this in mind, my great granddaughters are coming from Chicago for a visit, and I WILL meet that four o’clock train.” And Esther says, “Yes, Mizdawn,” the way she might have said it when she was Mizdawn’s pupil thirty years ago.

Esther is worried. “I’m just hoping I don’t have to call in SWAT and we can get him out…” And Mizdawn stops and says, “SWAT? For Chester Nash?! Maybe a fly SWATTER.” “It’s the gun, Mizdawn. He says he’s got a shotgun in there and nobody can come near the house.” Mizdawn shakes her head. “You call his son?” Esther nods, saying “He won’t come here, and it would take him an hour and a half, anyway, and Chester won’t talk to anybody on the phone.”

Mizdawn shakes her head again. “The man steals his lunch, and look at all this hullabaloo – police all over, and those people parking here and hoping to see somebody get shot. Who else is here? Jesus, is that Tattimer from the store? They hate each other, and why am I here? Because I taught him in high school?”

“He still talks about you – to anybody who’ll listen to him anymore. About how you two almost got married.” Mizdawn looks to the heavens. “Hah! Still that same old tattered fib. Good lord…” The deputy arrives and hands an electronic megaphone to the sheriff, and she holds it toward Mizdawn. “He can’t see you from here, so just… get him talking. Here, I’ll show you how to use that.”

Burt Mizdawn just sighs, a long, heavy one, and begins walking toward Chester’s house. “Wait! Hey! Don’t Mizdawn!” the sheriff shouts, but Mizdawn keeps going, making a waving sign for all others to stay back. She walks straight to the slightly leaning porch, steps up on the old boards, as Chester shouts from inside: “Who the hell’s there?! Goddamnit, I WILL shoot!” Mizdawn answers, “Oh, stop yelling, Chester. It’s me. You going to shoot ME?” There is a long pause before Chester answers in a much softer voice, “You can come in.”

But Mizdawn has hold of an old wooden rocking chair and is moving it in twists and turns, stronger than she looks, until the chair is beside the screen door. Then she sits. “This’ll be fine. I can barely see you in there.” The sun is striking the back of the house, while the front is deeply shaded, so that the outline of Chester barely registers in the gloom. “Turn on a light or something, will you?” she asks him. “No. If they can see me, they can shoot me.” “Nobody is going to shoot you, Chester. Do you really have a gun in there?” Chester says, “Never mind,” and then, in heartfelt words, “Thanks for comin’ here, Mizdawn.”

“I was brought here--sheriff’s orders.” She looks over the worn-out house, fallow fields. “Why are you still here, Chester? Why not sell it off and get yourself to McHenry and that home there?” “Where people go to die,” he says, and she answers, “Well you wouldn’t die alone.” He pauses a while. “Used to think…maybe my son would have this place someday. Never gave him much. Did they call him, Mizdawn, about…all this?” she answers “Yes,” and then, “He’s not coming, Chester.” The man sighs. “Don’t blame him. I made a sorry father.”

She puts her hands on her knees, leaning toward the screen door. “Listen, now. Why did you steal those groceries? To get your son here?” “No, Mizdawn, to get a good meal for once, a really good meal. That Tattimer is pricing me right out of his store, and my truck can’t make the highway to the Albertsons, so… I got a fine wine in here. I can pass you a glass.” “Not in the middle of the day, Chester, and in the middle of a shoot-out. So, now your good meal is over, what’s next?” “I don’t know that, Mizdawn. I don’t much care. I ain’t goin’ to jail though.” “So what does that leave, Chester?” “I don’t know what it leaves, but I’ll shoot my brains out before I get arrested.” “Shoot your brains out? What if you miss? That’s a pretty small target.” She doesn’t get an answer, and then hears a sound from deep in his chest, a quiet laughter. “God, I still love you, Mizdawn.” “Oh, that’s right,” she says, “We were going to get married – so YOU say. It was one brief kiss, old man, and that’s all.”

He seems not to hear that, going on. “Everybody in the school liked you, almost. We thought it was so excitin’ havin’ a teacher who was an Indian.” Mizdawn breathes a tired sigh. “You mean Native American, Chester.” “Aw, I know. It just takes too long to say that.” “Listen, you’re not all that busy, old man. I think you have the time for three more syllables.” From the darkness inside the house, she hears his quiet laugh again. “I could never get away with anything with you,” he says. “I could con the other teachers, and in the Army I could even con my sergeant. But not you. So…why didn’t you wait for me? Why’d you go marry that Mr. Netter?” “Why? Because he was a good man and we made a good long marriage, raised a fine daughter. There was love there.” “But you knew I loved you, Mizdawn, and I hoped… you’d wait.”

“And your hope was based on what, Chester – all the letters I wrote you?” He half-shouts. “You never wrote me one!” “That’s my point. I never led you on. I let you give me one foolish kiss, even then you tried for more: high school senior all hot with the girls – not with your teacher, not with this Native American.” “So…Mizdawn… why’d you kiss me at all?” “I didn’t. I let YOU kiss ME.” “But why?” “Because you were going away to probably get killed in a war you didn’t even understand, and you started to cry, all choked up.” “You enjoyed that kiss, too,” he says. “I know you did. I felt it. I…” “Chester, you had a boy’s crush on your teacher.” “Hell, Mizdawn, you were only five years older.” “And you were a child. You’re still part child, aren’t you?” “So… all you felt was kindness for me.” “There was caring, too. And sorrow. I saw your parents, your meek mother, your angry father, I saw his marks on your face more than once. Yes, kindness, so that’s why I’m here, Chester, and I’ll go talk to the sheriff and say you’re giving up your gun and…” “No! I’m givin’ up nothin! Let ’em come for me, and I’ll take some of ’em with me!”

At this, Mizdawn rises, moves quickly to the screen door, pulls it open and steps inside where the sunlight doesn’t reach, and there he is, in a chair he has moved to watch the door. There is no gun in sight. She steps close and slaps his face, hard, his eyes and mouth opening wide as she rails at him, not shouting, but sharp-voiced with a flame in her eyes. “Goddamn you, Chester Nash, how dare you talk about killing people, killing deputies and a sheriff that never harmed you, killing people with wives and husbands and kids? That’s cowardly talk and ugly and stupid, and if that’s what you have in mind, I’ll get your gun and shoot you myself! Where is it? Show me!”

He stares without speaking, tears coming, filling his eyes and moving down his pouched and craggy face. He only breathes and swallows, and then, finally, he says a cracked and liquid word. “Sorry.” His chest shakes and he swallows again. “Sorry, Mizdawn.” She slowly relaxes her body, taking a step back. Her voice is in a normal key when she asks, “Where’s the gun?” “It’s… on the floor, by my foot. It’s loaded, too.” She looks at the old shotgun, then studies him a while more. “Stand up, Chester.” “I ain’t goin’ out there, Mizdawn.” “Just stand up, old man.”

His standing is not fluid, but a series of stiff moves, and then he is facing her, a head taller, as she faces him, working on something in her mind. “I’ve got an idea,” she says, “how this can go, with nobody hurt and maybe you not in jail. You might lose an acre of land, but you have to do what I say.” “An acre of land?!” “Chester, you have to promise.” “How can I promise if I don’t know what else you’re talkin’ about? I ain’t gonna pologize to that bastard Arnold Tattimer. And I ain’t goin’ to jail.” “Damn it, Chester, you just have to trust me.” “Without knowin’ what you’re gonna do?” “Yes.” “Well, why should I do that, Mizdawn?” “Because if you promise to do as I say – I’ll kiss you here and now. I’ll kiss you one more time, Chester Nash.”

He stares a long while, his eyes moist, and says only one word. “Really?” And she nods, and takes his heavy hands in her hands, keeping her stare on him.

“I haven’t always told the truth, Chester. Mostly, but not always. I didn’t admit to wanting you to kiss me that day you came to my house, and I’ve never said that… that it was a great kiss, and that I felt the tenderness of it and the need and the thrill of it, too. I was a lonely young woman and a plain one, and you were this… kind of child-god. You were beautiful and strong, and I was alone. People were kind enough to this Potawatomi girl, but they kept a distance. And there you were, loving me all-out in your young way and wanting me, and I joined you in that kiss. I know you felt that. I didn’t let it go further. I was your teacher, for god’s sake, but for that long minute I was thrilled, Chester. I told you that was the beginning AND the end of us. I told you that, but you didn’t want to believe it, wouldn’t believe it, and I went on with my life, and Jack Netter came along and broke through, broke through to me, and we fell in love, all the way, and that was that. So… put your arms around me.” He does, gently. “Hold me tight.” He does, his hands on her back, their faces close now. “Remember,” she says, “Your hands on my butt are not part of this deal. You tried that once.” He nods, smiling through his wonder, his wonder of holding her again after 60 years.

Their faces float toward each other, heads cocking to the side, mouths coming close, and then there it is, the second kiss between Chester Nash and Ella Dawn. He keeps his hands on her back as he was told and she has one hand on his shoulder and one behind his neck, pulling him deeper into the kiss as he pulls her, until they make one mouth and she feels a fluttering in her chest and he feels a great pull of love and desire and they both close their eyes and swim for a moment in the past, becoming the boy again and the young teacher.

It's she who begins a settling, a slight relaxing that signals the man, and so he settles, too, somehow easing himself back from that most splendid minute of fulfilled desire, and then they’re staring at each other, eyes full and minds slowly pulling them back from a summer day in 1950 to today, where the police and the neighbors are waiting and watching for them, and there is a loaded shotgun on the floor.

“Now Chester, you promised. I’m going out there, and you just have to trust me.” He nods, unwilling to speak, to completely give up the moment still filling him. She steps back and looks around, seeing a table still littered with plates and the leavings of his stolen lunch. She walks to the table. “You didn’t open this box of candy.” He manages to say, “No,” still in a spell he doesn’t want to break. “Well, that’s something.” She buries the candy box in her large purse. “Now you trust me and you don’t go near that gun.” He gives her a nod, but she doesn’t accept it. “Say it, Chester.” “Okay, Mizdawn. I won’t touch the gun.” She nods then and turns, opens the door and moves down the steps. He has moved to the door and calls out to her.

“Mizdawn?” She stops and half-turns, waiting. He says, “About my son?” “Yes, Chester?” In a moment he adds, “I wasn’t a good father, but never hit ’im. Never.” She nods a while and says, “Good. That’s good,” and then she walks on.

As she reaches the side of the house she notices they have all gathered around an old, forgotten picnic table, which is a-tilt and is covered with decades of bird droppings, and she joins the group there, facing the sheriff, two deputies, Arnold Tattimer, and a man taking photos for the local paper, and even the mayor, Nell Wentworth is among them.

The sheriff is speaking to Mizdawn as she joins them. “Jesus, Mizdawn, you scared the hell out of all of us. What kind of state is he in?” And the mayor asks, “Did he harm you?” “I am unharmed, Nell.” “Did you see the gun, Mizdawn,” the Sheriff asks, and the young man there takes her picture. “The gun is on the floor near where he sits. He never touched it, and I think we can resolve this whole mess in a few minutes.” Arnold Tattimer points his finger at her like a pistol and says, “We can resolve this when Chester Nash is in jail and I’m paid back for every penny.” “What’s the tab, Arnold?” Mizdawn asks him, and he answers “One hundred thirty-six dollars and twelve cents, and I’m going to sue him for what he put me through.” “He never even spoke to you and never touched you,” the sheriff puts in, and Arnold says, “Emotional trauma,” and the sheriff says, “Let’s focus on the situation,” and turns to Mizdawn. “What’s gonna get him out of there?” but Mizdawn has a question of her own. “What’s the charge, Sheriff, and what’s the penalty?”

The sheriff takes a breath. “First time shoplifting, no jail, fine of $150, plus possible penalties and adjustments.” “And I’m pressing for the FULL charges and penalties,” Arnold says, and the mayor jumps in. “Stop interrupting, Arnold. Let’s solve this. There’s a TV crew on its way from Waukegan, and I don’t want to see our town looking at its worse.” “I agree,” says Mizdawn, rummaging in her purse. They all watch her. She comes up with two twenty-dollar bills. “Let’s pay Arnold what he lost and get him out of here. That’s a start.” She puts her forty bucks on the table and looks around at the others. “Yes, fine, it’s worth it,” says the mayor, and places a credit card on top of Mizdawn’s bills. “Fifty out of that,” she says, and they all glance at each other. The sheriff, sighs and digs out her wallet. “All right, damnit, thirty more.” Arnold is staring at the pile as he adds it up. “Still sixteen dollars short,” he says, and Mizdawn stares at him. “Among the wine and steaks, Arnold, wasn’t there a box of candy?” “Hell yes, twenty dollars and change just by itself.” Mizdawn digs in her purse again, brings out the unopened candy box and places it on top of the money. “You’re about four dollars ahead, Arnold.” “Hell, what about what I’ve been through, and…” The mayor cuts him off with “Damn it, Arnold you take off NOW! If you don’t, I’ll never shop at your store again and neither will my friends, and I have a lot of friends, so goodbye, and I’ll come by for my card later. We have to move this along!

As Arnold walks to his car, mumbling, the sheriff turns back to Mizdawn. “We still got a fine of $150 – and a hell of a lot of trouble caused and county resources used.” “I know, Esther,” Mizdawn says, “but Chester is making a peace offering that’ll cover it all and more. He’s selling off an acre of this farm land. The one the high school wanted for an extra practice field, and the town of Perch Lake can now purchase that acre at half the going price. I’m sure that once the sale is made, Chester will pay back your money, and you’ll both get a thank-you from all of us citizens, and from the students at the high school.” The sheriff stares at Mizdawn, growing a small smile. “Still looking out for your school, Mizdawn.” Then the sheriff and the mayor look at each other before they both turn and nod to Mizdawn.

Chester is still waiting behind the screen door when Mizdawn comes to the house and up the stairs. He opens the door for her to come in, but she stays put on the porch. “All done, Chester Nash. You’re going to have to put up with the sounds of school children on that far acre that you’re going to sell at half market price, but that won’t be so bad, will it? You’ll make some money, buy a new truck.” He grows a smile, a loving smile, as she says, “Now hand me that gun, and it’s all finished.” He leaves the door and returns with the shotgun, hands it over. “It’s a heavy damn thing,” she says. “Want me to carry it?” “Oh no, Chester, we don’t want you carrying a gun to the sheriff. I’ll deliver it, and so long. You going to be all right, old man?” He nods. She turns and begins walking away. He raises his voice to say, “I love you, Mizdawn. You sure are one fine Native American.” She stops and lets him see her smile, then moves off toward the sheriff and the mayor and the deputies and an arriving television crew that will have nothing at all to do.

#

Choice

Welcome to “Short Stories” not necessarily for “Shut-Ins” anymore. Something here for June to help you decide what you want to do with this bright month, to help you make a CHOICE.

CHOICE

By Gerald DiPego

Ben Schulman is 32, single, fairly fit, and nervous. He has an important decision to make and he’s not at all confident that he’ll make the right choice. He has made some poor life choices in recent years, and this has left him with an easy-access pass into the thicket of worry, a place of thorns that he knows well, and, as he walks among the morning throng of downtown L.A. workers, his jaw is tight and his pace is quick, even though he’s early for his job at the accounting firm. He’s actually too early to show up for an important meeting with his boss who is waiting for his decision, and that’s why he keeps walking this fast-paced jagged circle through the canyons of downtown, giving himself one last bit of time to think about his choices.

He has been offered, along with other accountants, the possibility of transferring to the new offices opening in Portland Oregon, and being part of the start-up there with a small raise, or he can choose to remain in L.A. He doesn’t have full confidence that the new branch will do well in Portland, and he could be struggling there for years, but since the firm picked him for this, would a choice to stay in L.A. seem ungrateful and cost him points with his boss?

He’s moving across a street on a green light, among a swarm of office workers who are coming and going, and he notices that one man is approaching him as if they’re about to collide. Ben tries to angle to the right, but the throng is tight, and the young man is coming on quickly for this possible crash, but then, at the last sliver of a second, the man moves slightly to miss him, brushing against him, glancing at him, and saying these words…

“Stay in LA.”

Ben is standing still in the center of the street, his mouth open, his eyes drilling into the back of the hurrying man, when he finds that he is finally able to shout. “Hey! Wait!”

But the man keeps walking, and Ben tries to follow, turning against the herd of workers who are speeding to cross before the light turns green and the cars, waiting like high-strung horses, rush the intersection.

He has lost sight of the man, but he shouts anyway. “Wait!” And some people turn to follow his look, which is a wild, frenzied, unbelieving look, but the man is lost among the crowd, and Ben, now standing on the corner, is moving, in his mind, through all the possible causes for this impossibility: He didn’t hear the man correctly. The man wasn’t talking to him. The man was telling EVERYBODY to stay in L.A. because…because it’s a great town, or…. But none of this feels right. The man spoke to HIM, and said what HE needed to know. He couldn’t have imagined it, could he? No, it was so clear, and he still carries a detailed picture of the man in his mind, like a sharp and precise photograph.

“Stay in L.A.” He remembers the quality of the man’s voice and tries hard to think if he ever saw him before, but no, never. He wonders, oddly, if maybe the man has something to do with his accounting firm. But that’s crazy. Ben wasn’t even near the firm’s building when it happened. He was blocks away and moving in the wrong direction. So, here he is, standing on this busy corner and shaking his head, which is the only option for this situation.

He continues on, but more slowly, aiming himself toward the streets that will take him to the firm, and once there he’ll proceed to his boss’ office, and there he will be asked for his answer: take the Portland offer or…stay in L.A. He is surprised to realize that he’s not so uncertain now. He knows what to say, and this is a great relief. Of course, he’s not completely sure, but he’s not completely lost, not drifting anymore. He has something to hold on to – those three quick words, no matter how they came to him. He holds them tightly and enters his office building.

It’s two years later, and all of this has happened to Ben Schulman: He gained 14 pounds and then lost it – He noticed some hair loss – He was promoted at work and was glad he did not go to Portland -- He met a young woman named Amelia and they dated and became a steady couple – He found a small, appealing house and was thinking of buying it and asking Amelia to move in with him – He bought an engagement ring – He was wondering just how and where and when he would ask her, when she told him, sobbing, that she was seeing another man, an old boyfriend. She was very sorry – He and Amelia broke up.

Ben is depressed of course and also nervous again. He really likes the small house he found in Santa Monica, and knows it will be off the market soon if he doesn’t buy it, but, will living in the new place further depress him because he’ll think of Amelia, who will not be there to share it with? It’s a property that will only increase in value. As an accountant, he would advise a client to buy it, but he’s afraid of being even more sad than he is, if possible.

He’s at a mall now where he often goes, looking for furnishings that would look very good in that new home and then not buying them. He has it almost fully furnished in his mind, still looking for the perfect sofa to not buy. He finds the sofa and feels a moment of joy that’s pushed aside by a wave of sadness, so he walks toward the mall doors to get out of there, outside into the sunshine. He steps back to let an older man enter, and the man looks at him in passing, not smiling, and says, quickly “Buy the house,” and then he keeps walking on. Ben watches him go, his mouth open. He starts to follow, but the man is walking swiftly, and the mall is very crowded. Ben hesitates, remembering, of course, the last time some stranger told him what to do.

Now he sits in one of the chairs outside the mall, in the sun, his brain whirling. He becomes truly dizzy and closes his eyes, takes several breaths. When he opens his eyes, he feels better. He sits a long while, then pulls out his phone and calls his realtor and makes an offer on the Santa Monica house.

Four months later Ben is in a bar, deep within the jolly cacophony of a Friday night. He’s with one of his best friends, Jim, from work, and he’s telling him more about the house than Jim cares to know.

“Enough about the house,” says Jim. “That’s all you talk about lately. I’m supposed to care about a hassock? What else is going on in your life?” Ben laughs and apologizes and then, as he finishes his second beer, he finds that he’s in a bold, why-not mood and says, “I never told you WHY I bought it. It’s because somebody told me to. Some…stranger. Really.” Jim, looks at him doubtfully. “So what did this guy know about real estate? Why trust HIM?” Ben is smiling, tingling even, he has never told anyone about these encounters. “He just told me – ‘buy the house.’” Jim grins now, “You mean like he was giving you a tip? like he goes around giving tips? Like…a tip on a horse? What is he, a guru?”

Ben looks at Jim, staring deeply, as if weighing his words. He’s losing his smile, moving inward, wondering about something, something about the words ‘A tip,’ and he’s deciding two things – that he will not tell Jim or anyone what’s going on or…where he’s going tomorrow.

The next day he goes to the Santa Anita race track, feeling guilty but excited. What IF one of these people…these people who talk to him and tell him what decision to make, what if one of them is there, the man from the street, the old man from the mall, somebody. Maybe they WILL give him a tip. But no one talks to him, and he loses 70 dollars.

At his second visit to the track, he is moving through the betting area, listening, while reading about the horses who are running. He is also glancing at the swim of faces, but, mostly, he’s waiting, waiting for someone to…

“Fancy Danny.”

He looks around quickly to see who spoke. It was a female voice, and he spots an older woman, maybe sixty-five, standing among the crowd, alone, studying her choices. He walks to her, his heart picking up its rhythm. “Excuse me, did you say Fancy Danny? I see he’s running in the next race.”

She looks at him a moment, slightly bothered and says “I said nothing at all.” But Ben is sure that it was her voice he heard. He repeats the name, “Fancy Danny,” and now she’s angry. “If you keep bothering me, I’ll have you thrown out of here.”

Ben gets in line at a betting window. He’s trembling slightly as he pulls out all the cash he brought with him, one thousand dollars, and puts it on Fancy Danny to win, even though the odds on the horse are thirty to one. He walks down to the rail to watch the race, his body tight and each breath shaking in his chest. He wins the thirty thou and ends his gambling days. He doesn’t want to be greedy and he doesn’t want the strain. He buys a new car and two expensive suits.

He is promoted again at work and he feels that part of the reason he was noticed and advanced is because of his high-end suits. He’s promised a larger office. He begins a love affair, but mostly in his mind. She’s a very real young woman, another accountant, same grade as him. Her name is Emily Woo, and, to him, she is beautiful, but she attracts the attention of other men, also, and the boss of Ben’s section of the firm seems charmed.

Ben speaks to her now and then, greetings, work details. She’s very pleasant and has a very real laugh that he begins to treasure. He asks his work friend, Jim, what he knows about her, and Jim says that she dates now and then, but the boss has shown an interest, and this keeps the sharks away.

The boss is married, has kids, but is very smooth, and Ben is worried. Should he just…ask her out and chance it? He’s afraid she’ll say no and that will kill all those possibilities dancing in his mind. He’s also afraid that the boss will find out, and that could hurt his career, just when things are going so well.

He begins taking long walks during lunch and even showing up early to the downtown area to move through the throngs and… wait for a tip, wait for that next ‘teller,’ wait and hope for that certainty, that knowing what to do. The streets do not favor him with a tip, so he tries a nearby park and walks the paved lanes and grassy areas, and he listens, listens. He’s sometimes late getting back to work, and when he is at work, he watches for her, just to catch sight, and he makes up scenes where they’re together, laughing together, holding each other…

He’s back in that park now, and rattled, his breath short, his eyes raking over the faces again as he walks. He feels that he’s coming apart and he finds that he’s speaking under his breath, saying, “now, tell me, now.” People begin looking at him as he passes, and he realizes he has begun speaking aloud, “Tell me…say it…please!” He walks on, losing control, shouting, “Will you tell me?! Will somebody tell me?! You? You?” And people are staring, some smiling, some afraid. He stops walking, but the shouting continues and a small crowd gathers. He doesn’t know how long this lasts, but now a police officer is walking him to a bench and having him sit, talking to him as the crowd of ten, twelve, comes closer.

With great effort, he is able to calm down and to convince the cop that he is all right, that he’s sorry, that he won’t be shouting anymore, that he will rest a few minutes and then walk to his workplace. The cop asks the crowd to move on and most of them do, only a few linger, and then only one, a woman somewhere in her mid-seventies. Ben sits there breathing and noticing how she stares at him, and now walks close to him.

“I don’t listen to them anymore,” she says.

Ben, shocked, stares at her as she goes on. “We just have to stop listening. Can I sit down?” He is still staring, but he nods and she sits. They look at each other a long while. “It’s OUR life, not theirs” she says. “Understand?” Ben slowly nods and finally speaks to her, his voice breaking. “Who are they?”

“I don’t know,” she says. “I used to think…angels? Then maybe devils, then nobody at all. Maybe I was doing it, but…. I just don’t know. I just know we have to stop listening.”

Ben is nearly in tears now, asking “How…will we know what choice to make?” and she stares deeply and says, “Usually it’s the hardest one, the one that takes the most courage, the scariest one.” In a moment Ben sniffles, and nods. When he returns to work, he finds that they are ready to move his office to the larger one that was promised, and he spends the day moving – and watching for Emily Woo. He sees her once and nods and she gives him one of her smiles, one of her best.

The next day he comes to work in one of his new suits and enters his new office. It’s only one office away from the boss. He tries to look busy, but he’s watching the hallway, watching for Emily so he can seem to be just stepping out as she passes, and he can ask her inside to show her his new space, and he can ask her…really ask her to have dinner, make the choice and take the chance – and there she is, walking down the hallway. But the boss is with her, his hand lightly on her shoulder as they talk, smile, and move toward the boss’s office and enter.

Ben stands there, pinned as if shot with an arrow. He wants to retreat, but can’t move. He keeps staring at the boss’s closed door, tries to will her out of there, hoping, and, in two and a half minutes, the door opens again. The boss holds it open for Emily, both of them smiling. Ben doesn’t hear their words, but sees that the boss’s hand is now on Emily’s waist, just lightly there, and, as Emily steps out the doorway, the boss, who can’t be seen by anyone in the hall, drops his hand down to Emily’s ass.

Three things happen. Emily, surprised, turns quickly to the boss. The boss smiles, winks and closes the door. Ben steps deeper inside his office, rattled, hurt, disappointed, afraid to be seen. He knows she’ll be walking by his open door soon. He should sit at his desk. He should…. But she doesn’t pass his door and he can’t help himself. He peeks down the hall.

Emily is still standing at the door to the boss’s office, standing still, then she turns quickly and walks away, and Ben sees that she is upset and angry, shaken even. He steps back so she won’t see him, so he won’t be involved, so he won’t get in trouble with his boss and lose his position, so he won’t…. Emily walks past his office, her eyes intense, her jaw shaking. He hears her steps moving further away, and he suddenly knows what to do, all by himself. It’s the scariest thing.

He hurries out of his office and catches up to her. “Emily?” She turns to him, eyes moist, chin rigid and she says, “Can’t talk now, Ben” as she walks on, but he calls after her. “Emily, I saw that.” She stops. She turns to him. He nods, walks close to her. “What he did?” she asks, and Ben nods. She stares and then says, “I’m going to HR now, Ben. I might get fired, but….”

“Tell them I saw it,” Ben says. “Tell them I’m a witness.”

“Are you sure,” she asks, and he nods, and she smiles as best she can, and he basks in that smile, and she walks on.

The rest of the morning is calamitous: accusations and denials and statements to sign, but at the end of it, Ben feels good, actually very good. The future is in doubt, but, then, that’s the thing about the future. It’s always in doubt. He’s walking in the park now before leaving to go home, hoping to see the woman he spoke to on the bench and to thank her, but he doesn’t see her and now he’s just walking aimlessly, at an easy pace, when a teenage boy on a skateboard rattles toward him down the lane, coming very close, brushing past him and saying these words…

“Good Choice.”

#

Kilimanjaro

KILIMANJARO

By Gerald DiPego

Tanner Schiff and Faya Ramon are both 74 and have been friends for 17 years, part of a foursome. Tanner was married to Gwen and Faya to David. Gwen left Tanner five years ago. David died two years ago. Tanner and Faya are unmarried and continuing their close friendship, an unbreakable law of dinner once a week at his place or hers with long talks, and sometimes a movie on television before they part for another week.

They are at Faya’s tonight, finishing dinner. Tanner has poured himself a rare third glass of wine, and, as they sit on the sofa, he keeps staring at her.

FAYA

What?

TANNER

What d’you mean, ‘what?’

FAYA

You’re staring at me.

TANNER

I have something to say.

FAYA

Obviously.

TANNER

What if I….

(There is a long pause.)

FAYA

What if you what? Am I supposed to guess?

TANNER

That would help.

FAYA

Give me a hint. What if you…? Went to Istanbul…wore a cowboy hat…?

TANNER

Faya…what if I didn’t go home tonight?

FAYA

You mean…. You don’t mean…. Oh, god, Tanner…. Oh, no…. Can’t you just…can’t you just go to Istanbul?

TANNER

What if I stayed here, all night?

FAYA

It’s the wine. You had an extra glass of….

TANNER

For courage, yes.

FAYA

Tanner…Tanner…let’s not go there. Now? Let’s not ruin this. After all these years? What we have is so… special and very important in my life. And now? Sex? Really? At this age?

TANNER

Yes. Now. It can finally be our turn. You know I’ve always loved you, and you….

FAYA

After all these years you want to take me to bed? Why? Why now? Is it something like…climbing Mount Rushmore before you die? So you can say you’ve done it?

TANNER

Nobody climbs Mount Rushmore. You can’t climb Mount Rushmore.

FAYA

All right then – Kilimanjaro. What am I, an alp? You have to plant your flag?

TANNER

I’ve always wanted to plant my flag with you, but there was Gwen and after Gwen there was still David and now there’s no one between us. This isn’t some wild thought. You can’t say you never wanted us to be lovers because I saw…sometimes I’d see you look at me that way, and I looked at you, and we KNEW. And now two years have gone by....

FAYA

So, what is that, some ‘sell-by’ date? Now or never?

TANNER

Yes! Waiting more than two years goes against all human law.

FAYA

Waiting? I haven’t been waiting. You’ve actually been waiting?

TANNER

Yes! And imagining. And wanting and….

FAYA

Thinking about this…what…every day?!

TANNER

Mostly at night. And there’s nothing to stop us now.

FAYA

Age, Tanner and…the thought that we could lose what we have, and I need what we have. I treasure it. Please, PLEASE go to Istanbul.

TANNER

You know what I’ve been thinking of?

FAYA

Stop thinking.

TANNER

We were all at the beach, oh, what, a dozen years ago? And…your bathing suit slipped down. I must have been…58 or so, but I felt…like a boy, a teenager getting a glimpse of….

FAYA

They don’t look like that anymore, Tanner. For god’s sake…and you’re not a boy!

TANNER

I am, that’s what I am with you. I’m this love-struck, aching boy. So, tell me now. Tell me once and for all. You need me in your life, but you don’t want me in your arms? In your bed? Faya, are you through with sex? Do you never have those feelings? Aren’t there times…?

(She closes her eyes. She sighs. He waits.)

FAYA

Yes…times. Now and then.

TANNER

Thank god. When?

FAYA

Mostly…when I…watch a film.

TANNER

A film? What film? You mean…any film?

FAYA

No, you idiot. A film…with…

TANNER

With what?

FAYA

With Javier Bardem.

TANNER

Oh, for god’s sake.

FAYA

It’s his eyes.

TANNER

He’s not real! I’m real and I love you and want you and…it’s time for us. Finally.

(She stares at him a while, her eyes moist now, taking him in, her Tanner.)

FAYA

When Gwen left you for that…ridiculous man, I wanted to hold you and rock you. I did hold you.

TANNER

Yes. I remember. I loved that. It was like CPR. You held on…. You did actually rock me. You saved me.

FAYA

Yes…and I DID want to take you to bed.

TANNER

So you wanted that.

FAYA

Oh, yes. I would weep for you. David heard me at night once or twice and he would ask me, and I would say, “I’m just so sad for Tanner.” Maybe he guessed about my feelings for you, but he never said anything about it, and I never DID anything about it, and now it’s way too….

TANNER

And when David was dying, I was hurting for both of you, and….

FAYA

You were great. You were with us to the end….

TANNER

Yes, but oh, how I wanted to take you away somewhere after all the gatherings and the memorials and the pain, take you far away and bring you peace and love you in every way. But….

FAYA

But we didn’t, and so we held on to what we had. What we’ve always had, and now here you are, shaking everything loose. We could get hurt, you know. We could be giving up something fine….

TANNER

And safe.

FAYA

Yes. Why chance it – at this age?

TANNER

Maybe that’s the point?

FAYA

What’s the point?

TANNER

Now or never – because never isn’t so far away anymore.

FAYA

What if it’s a disaster? Could we come back from a disaster?

TANNER

Don’t say “disaster." You’re jinxing it.

FAYA

Could we come back?

TANNER

I think we could. I think we should take the chance.

FAYA

Am I the only one who’s afraid?

(He stares a while. Then…)

TANNER

No.

FAYA

Well, thank you for that.

TANNER

You’re welcome. So…?

FAYA

So?

TANNER

Should I stay?

FAYA

You mean now?! Tonight?! God no. I need some time to…. I need some time to fit this into my brain, and…think of what to wear.

TANNER

Next week then. It’s a date.

FAYA

Is it? Really? I guess it is.

TANNER

A definite date.

FAYA

Tell me…would you have brought this up if you hadn’t had that extra glass of wine?

TANNER

I…don’t know. But I’m glad I had the wine. And now…let’s be brave. Without any wine.

(She stares a long while, eyes going deep.)

FAYA

So, we’re really doing this?

TANNER

Yes. Please. My place?

FAYA

No. Here.

(He kisses her forehead, then they lightly kiss on the mouth, and he stands.)

TANNER

Maybe you’ll think about me in bed before you sleep tonight.

FAYA

Are you crazy? Who’s going to sleep tonight? I won’t get any sleep for a whole week.

TANNER

Maybe…it doesn’t have to be a whole week.

FAYA

Really?

TANNER

What’ll you be doing tomorrow evening?

FAYA

My granddaughter is coming over to teach me how to put a Zoom together, so…

TANNER

Tuesday I’m giving that talk at the Rotary.

TANNER/FAYA

Wednesday?

(They stare, sigh.)

FAYA

Dear lord.

TANNER

Wednesday evening here. I’ll…bring sushi.

FAYA

I’ll make a salad. Listen to us. So…normal.

(They share a soft smile, move to the door, one more long look. Then he leaves. She sighs again, worried, wondering and…in her eyes, there’s a nearly invisible glow.)

--------------------------------------

Wednesday evening has come. Faya’s doorbell rings. She moves to the door, taking a deep breath, then speaking through the door.

FAYA

Tanner?

TANNER

No. It’s… Javier Bardem.

(She opens the door. He’s standing there with a bottle of wine and a bag of Sushi choices. He’s nervous. So is she. She wears a kind of billowy caftan, covering her from neck to ankles. He’s in a suit with a colored shirt, open at the neck. They both take a deep breath. Soft music is playing on her sound system. She looks him up and down, sternly.)

FAYA

You’re not Bardem.

TANNER

No, he… couldn’t come. I’m the man with the sushi.

FAYA

Well, you might as well come in.

(He walks in and moves toward the sofa where plates and a salad are set out on the coffee table, also water and wine glasses. He places the bag and the wine on the table, studies her.)

TANNER

You look beautiful.

FAYA

No, I don’t. Do I? I didn’t know what to wear.

TANNER

Me neither. I did shower though…twice today.

FAYA

Thank you. I bathed.

TANNER

Oh.

FAYA

“Oh.” Meaning…what?

TANNER

Well…that’s nice. Bathing. It’s sensual. Maybe some…relaxing, scented bath salts, maybe some very…very smooth cream for your skin….

FAYA

I put the cream on the night stand, for us. In case….

TANNER

You did?! You really did that?!

FAYA

Yes.

TANNER

That’s a wonderful idea!

FAYA

Don’t lose control.

TANNER

Of COURSE I’m going to lose control. That’s why I’m here. Won’t you…lose control?

FAYA

I don’t know. It…depends.

TANNER

Oh, god – it depends on me, right? Is that fair? What if I fail? It’s been years!

FAYA

I believe it’s a shared responsibility, Tanner.

(He sits on the sofa, staring at his thoughts, worried.)

FAYA

What?

TANNER

I, uhh. I think I’d like some wine.

(He rather hurriedly opens the bottle. She sits beside him.)

TANNER

I brought white because…because of the sushi.

FAYA

Yes. White is fine.

TANNER

Are you nervous, too?

FAYA

Not at all.

(He pauses in mid-pour, staring at her.)

FAYA

Of course, I’m nervous, Tanner! Of course. I’m jumping inside. I couldn’t decide on the music. Do you like the music?

(He fills the glasses, listening to the music.)

TANNER

Uhhh. Really? Classical? It’s a little heavy.

FAYA

You would prefer what…Grunge? Ska?

TANNER

Ska would be good.

FAYA

It would?